Dancing with Daisy May

A Scottish story from exactly a century ago

A chàirdean,

Welcome to a new year. I hope it offers you more freedom and less trouble than the last. Here’s a wee history essay I began some years ago and am glad to finish for you now. It’s a special story to me.

On a warm summer night in 1924, at a concert in the small Scottish town of Linlithgow, where the wide and shallow loch offers up a mirror image of the birthplace of Mary, Queen of Scots, the railwayman Joe Williamson danced with the singer Daisy May Clifton. They danced close, and late into the night Joe leaned in for a kiss — or perhaps, as Daisy May, summoning all her graciousness, later told the papers, he merely and accidentally brought his face close to hers. Either way, she drew back and reprimanded him for his presumptuousness. I imagine that this, on her part, was a quick reaction to the immediate danger, the instinct of self-preservation at work. I imagine that she held him at a distance so that she could study his eyes for a glimmer of understanding. I imagine that she saw herself reflected in those eyes, and fell.

Chided into doing things properly, Joe invited Daisy May for regular walks around the loch, a popular activity for local courting couples. It was a walk public enough not to be seen as improper, and very beautiful besides, but of course there were plenty of leafy woods all along the path into which couples could sneak. They walked, and talked, and maybe more, and Joe went to see her sing in local concerts, where she was always the star of the show, with her clear and high voice. They walked out for some weeks, but the strain of the courtship, always attended by fear, was too much for Daisy May: she broke off the liaison. Still, she nodded politely to him whenever she saw him at Linlithgow station, on her way into Edinburgh to perform, to Dalkeith to work as a painter, or to Bo’ness to meet men by the docks.

A year later, Joe saw Daisy May perform again, at a float on the annual Riding of the Marches, a centuries-old pageant in which the town’s leaders and citizens walk the legal boundaries of the township. Daisy May dressed as Dorothy Ward dressed as Aladdin. Ward was one of the most famous of British actresses at the time, known for playing the principal boy in pantomimes, that strange British form of popular theatre in which legends and fairytales are retold with cross-dressed actors, filthy jokes and topical humour. In 21st century pantomime the principal boy, a woman playing the heroic lead, is usually left out, but the pantomime dame, a man playing a matronly comic role, usually still appears. Ward played principal boys from Prince Charming in 1906 to Dick Whittington in 1957, when she was 66. Pantomime cross-dressing is in a lineage with contemporary drag and Edwardian male and female impersonation, but emphasises parody over verisimilitude: the true sex of the actor should always be clear, mocking the performance of the costume. So when Joseph saw Daisy May in 1925, he saw a woman dressed as man, dressed in that thrilling way that emphasised her femininity via her transgression.

They began courting again. But this time, Joe needed a bit more clarity. Why did Daisy May sometimes dress as a woman, sometimes as a man, and sometimes as a woman parodying a man? Was it true that she had a job in Dalkeith under the name Davy Park, where everyone knew her as a man? Was it true that she was courted at the docks by men in Bo’ness, where everyone knew her as a woman? Was it true that she had a career in the Edinburgh musical halls, under the bizarre name of Madame Vi Morena, where she was known as a female impersonator, or “the woman with two voices”? What was going on? And which was she?

Daisy May swallowed, breathed, checked on the little trick she knew of keeping her larynx raised in her throat, as she had been practising since she was a teenager, for over 15 years, and explained that of course she was a woman, but that she pretended to be a man in Dalkeith because she needed a working wage. And yes, there had been other suitors, but nothing serious. And yes, she loved to sing, and had a wide range: wasn’t she known for her star turns in Linlithgow concerts? Hadn’t Joe heard her soprano? Joe accepted her story, and they began to meet regularly in Edinburgh, the capital city, where they would be safer from local eyes and local gossip. Sometimes Daisy May appeared as herself, and sometimes she dressed as a man. For money, she said. And maybe for safety.

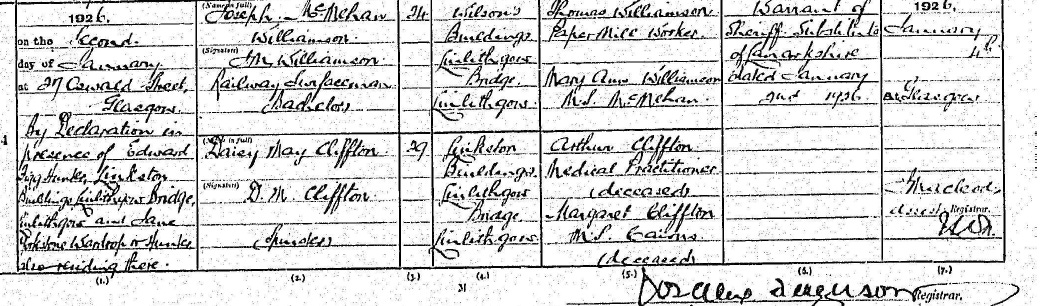

It was not a steady courtship. Sometimes Daisy May became mysterious and distant, and told stories about her work and her origins that never quite matched up. Sometimes Joe cooled off, distressed and confused by the rumours that reached his ears from Dalkeith and Bo’ness. But they were drawn to each other, and Daisy May must have felt adored by Joe, drunk on his attention, ready to refuse all caution, because after a few months she suggested marriage. He agreed. Maybe marriage would give them some stability. And when the arguing became too much, and Joe cooled off again, in the dark of the Scottish winter in 1925, Daisy May gave him an ultimatum: marry me now, or it’s off for good. He agreed, again. They made a date in the Glasgow Sherrif Court for a civil marriage. Daisy May’s Linlithgow landlady, Mrs Hunter, who knew her only as a talented if eccentric woman, charming, a real performer, agreed to be a witness, along with her husband. Two days after the drunken Hogmanay celebrations, on January 2nd 1926, they were married. Daisy May wore a pleated frock, an expensive fur coat, heavy boots, a black hat and a veil. Joe’s outfit is not recorded, but I imagine he wore the best suit he could buy on a railwayman’s salary, which would not be a good suit. I imagine that he was proud, and hopeful, with a little doubt gnawing away. I know that Daisy May was terrified.

She was right to be, because then everything unravelled. After their honeymoon weekend, Daisy May refused to move in with Joe and his Linlithgow family, saying that she wanted to wait until he had his own house. During the week she kept her room with the Fairgrieves in Dalkeith, where the landlady knew her as a female impersonator and the town knew her as the painter Davy Park; at weekends she rented with the Hunters in Linlithgow, where the town knew her as the singer Daisy May Clifton. But although Linlithgow and Dalkeith are on opposite sides of Edinburgh, they’re still only 25 miles apart, and word travels. Despite the private civil ceremony, without any family in attendance, news of the wedding spread, along with news of Daisy May’s reputation. Joe’s family got suspicious of the hasty wedding, suspicious of the rumours about Daisy May’s sex, suspicious of the even more salacious rumours about her many money-splashing suitors in Bo’ness, and demanded proof that she was a woman. Daisy May got a friendly doctor to send the family a signed statement of her womanhood, but this failed to convince anyone. Joe’s father, Joseph Senior, dragged Joe and his sister off to the Fairgrieves’, and summoned Daisy May Clifton. She came downstairs dressed as David Godfrey Park, looking resigned. Mrs Fairgrieve asked what on earth was happening. “It’s alright,” said Daisy May. “We’ve sent for a doctor.” “What for?” said Mrs Fairgrieve. “To examine me,” said Daisy May.

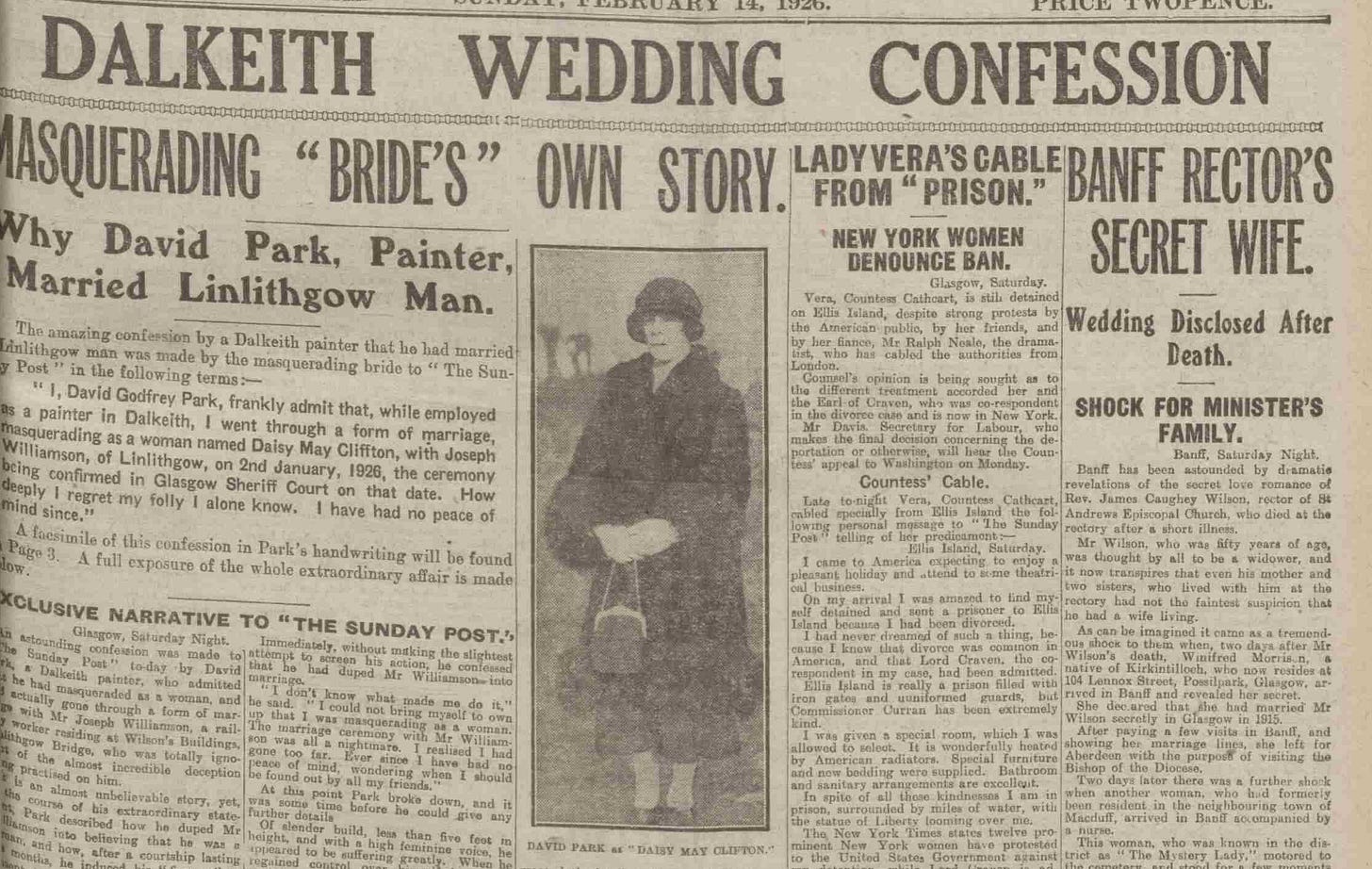

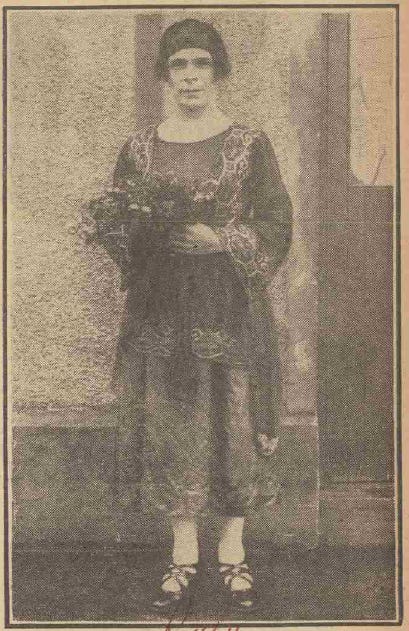

The detail of the doctor’s report is not recorded in the Glasgow Sunday Post, which broke the story on its front page, complete with photograph, on Saint Valentine’s Day, February 14th 1926, nor in any of the further news stories published as the story spread round the country in the following fortnight. But we can assume that the doctor concluded that Daisy May was a man, because that is what she told (and I suspect, given the photograph and interview, sold) the Sunday Post. The Post also spoke to people in Dalkeith, Bo’ness and Linlithgow, who reported that while Daisy May was only five feet tall, and very good at make-up and feminine voice, she was also bald and shaved twice a week. In the picture on the Post’s front page, she is wearing a big, dowdy coat and hat, and looking past the camera, her expression serious. In the Daily Mirror’s picture pages, two days later, she is wearing an embroidered blouse and skirt set, white tights, strappy shoes, a glamorous headband, and a wry expression. In both pictures she is named as David Park, or Parke. In both pictures, I can only see Daisy May.

What a story! A trans woman in small town Scotland in the 1920s, successfully courting and marrying a local labourer, only to be discovered, sell her story, and then vanish without a trace. Have you ever heard anything like it? You should have, if you’re paying attention.

Daisy May’s story was found by James Bates of the Gender Community Library’s Historical Crossdressing Project, who made the discovery by searching for key terms in the British Newspaper Archive. That turned up a single brief story in the Leeds Mercury, which I spotted on his map of historical cross-dressers, looking for Scottish entries. Curious, I put her name into the archive’s search, and there was the front page spread, and the photos. Daisy May stared right at me.

James learned this technique from Emily Skidmore’s True Sex, which explores the lives of eighteen passing men in the US 19th century. Peter Boag’s Re-dressing America’s Frontier Past digs further back into American history. James’s map uncovers an equally rich history of cross-gender behaviour in these islands, though not one for which I’ve yet found an academic survey. Wherever you look, you will find records of trans people: the problem is not that we’re not there, but that our stories are buried by neglect or misunderstanding.

Daisy May is, however, a particularly rich example. Our stories are more commonly found in police and court records; when we’re in the papers, we merit only brief and salacious write-ups in the papers. Much more rarely can we be found in our own words and posed for our own photographs: Daisy May is special because she can, however briefly and however compromised by the need to present a palatable and non-prosecutable story, speak in her own words. The Sunday Post story is one of the earliest trans tell-alls I’ve ever seen, made up almost entirely of Daisy May’s testimony, while the Linlithgowshire Gazette a few days later offers a tantalising picture of how she was seen in the town.

Her story also comes at a fascinating juncture: after the moral panic which led to the Labouchère amendment under which Daisy May and would have feared prosecution could be prosecuted (and in the passing of which the fear of trans women was key), but before Christine Jorgensen’s inauguration of the era of the media transsexual. A decade earlier Havelock Ellis had coined the term “inversion”, later to be most famously used by John Radclyffe Hall in The Well of Loneliness; the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft had been operating for seven years in Berlin; and in four years’ time Lili Elbe would go for her first surgey. All of that is to say, Daisy May’s marriage occurs at a changing and contested moment in trans history, when both “trans” and “gay” as medical categories and identities are beginning to emerge and separate from each other, and when media and legal approaches are in queer flux.

As far as I can tell, no-one else has written about Daisy May since 1926, where she turns up as a one sentence mention in Crook Janes, a popular study of female criminality by the briefly famous con artist Netley Lucas. I can find no results for any of the names involved in any academic search engine. There are eight news articles I’ve found in the archive, five of which copy their details from the Post, which has the only direct testimony from Daisy May herself; the Mirror then grabbed a second photo, and the Linlithgowshire Gazette conducted further interviews with other local residents a week later, and then that’s it.

Daisy May vanishes entirely from the record. I’ve also found no further stories of what happened next, nor any legal records for her various names (Daisy May Clifton or Cliffton, David Godfrey Park or Parke) beyond the marriage certificate. I first tweeted about Daisy May in 2021, and one Tiktok account seems to have picked up the story since. I’ve looked hard, and I can’t find her. Did she change her name? Did she emigrate? Did she keep living a life between genders? Did she find a way to live in only one? I want to know. I never will.

And who were Daisy May’s friends? The Sunday Post reporter found her living with friends in Glasgow, and she must have known fellow performers. Who taught her voice and make-up skills? Despite filmic portrayals of lonely and misunderstood misfits I live in a world of trans women, building lives and worlds together. I know about Fanny and Stella’s milieu, and can picture the world of the molly house, but I know nothing about Daisy May’s reality. What was the world of female impersonators in Scottish 1920s music halls like? Were other women walking the streets with her? Will I ever know?

As for Joe, he stayed in Linlithgow for the rest of his life, and much of his family stayed in West Lothian too. I followed them down the years through births, deaths and marriages Scotland’s People and free trials on Ancestry.com. There, I found a surviving relative, a nephew, who was conducting his own family research. I made contact, understanding the sensitivity of what I was about to share. I asked what he remembered of Joe. “He was a quiet and private man,” said this stranger on the other end of the internet, only a few miles away from me. “And he never married again. I think perhaps now I understand why.”

The story I told above is drawn directly from the two primary newspaper articles with a few projections from me of emotions, settings and motivations. By this account, she only dressed as a woman and got married as an extension of her stage persona, a turn gone too far, and Joe had no idea. She said, “My mother was always warning me against my fondness for masquerading as a girl, and though I have often gotten myself into slight difficulties before, I never believed that I could be such a fool as to go to the lengths I have done this time.” This is the story she told the newspapers, casting maximum blame and regret on herself, and maximum ignorance and innocence on Joe. The Post corroborates many of the details with testimony from witnesses, a signed statement from Daisy May, and a copy of the marriage certificate. Whether that story is the truth is another matter.

The Linlithgowshire Gazette sent a reporter to conduct further interviews and find out more salacious details, including of Daisy May’s many “suitors” in dockside Bo’ness “who usually saw to it that their young lady was gallantly supplied with expensive boxes of chocolates” or who met Daisy May “in a quiet lane to the rear of the town”. The innuendo throughout is that Daisy May was engaged in sex work, and that most of the town knew about her trans status and were titillated by it – until she went too far. Some men seemed to know and like it, some men seemed to not know and like it, and some men seemed to hate it. She was having a wonderful time, dressing in fabulous outfits every night and making every head turn. One told a policeman to arrest her. “Haven’t you heard of a hermaphrodite?” said the surprisingly informed cop. “Keep an eye on him either way,” said the clype. Is any of this story any more true?

There is another version of the story we can easily imagine, one which seems a little more credible than the one Daisy May sold the papers. Surely Joe knew of Daisy May’s trans status all along, or at least from an early stage? Surely they didn’t just walk and talk by that loch? Surely they slept together, skin to skin, on their honeymoon weekend? Surely the pair of them had hoped to live a married and heterosexual-to-appearances life together? Perhaps when Joe’s family started causing trouble, when the lovers realised that either or both of them might soon be prosecuted for gross indecency, they concocted together a story: Daisy May had merely gotten carried away with the prank, Joe was the harmless fall guy, and they had certainly never had sex. Daisy May would tell this story to the papers to protect them and satisfy Joe’s family. After all, it worked for other cases documented in the courts and reported in the papers, Fanny and Stella included: “it was only a harmless joke that got out hand”. Maybe, when the gossip died down, they would run away together and try again. Why didn’t they run away together? What did Daisy May do? What about Joe?

We could tell any of these stories as either gay or trans, and it doesn’t make any sense to tease those identities apart, not when at the time they were entwined. Saying “Daisy May pretended to be a woman to provide social cover for homosexuality” erases the obvious trans reading of these events, Daisy May’s evident delight at living as a woman in Linlithgow off-and-on for years, and her comment in the Post about long-term cross-dressing. Saying “Daisy May was a trans woman and Joe Williamson loved her as a woman” erases the complexity of gay-trans historical identifications, and Daisy May’s parallel life as a man, in which she did also meet Joe. I don’t think it really matters: Daisy May loved living as a woman, at least sometimes, and loved being loved as a woman, at least sometimes, and so she’s a sister to me, whatever else was going on, however she saw herself, and however Joe saw her. None of the terms work, because there was no settled term for Daisy May at the time, and we don’t know what she called herself. I choose to centre her femininity in the language of my telling to honour that sisterhood: I call her a trans woman in all the expansiveness that term might, in a better world, offer. What she wore at home, when no-one was looking, and what Joe called her in bed, barely matters to me — what matters to me is if he loved all of her.

I love both of these stories: the one in which Daisy May passed so well, and was so beautiful, that she convinced a man to marry her, and when things got too hot she sold her story and flew the coop to have more fun elsewhere; and the one in which two queer lovers did their best to make it, did what they needed to do to protect themselves when the public image unravelled, and hoped to build what life they could in the future. There are other stories, where Joe turns violent, or where the community turns violent, and then all the details are covered up, but I choose not to tell them, this time.

“It was just a joke” was the defence against gross indeceny prosecution for both parties in a queer sexual liaison. You’ll see it spread all over the crossdressing map. “We were only dressing as women, and not anything more sinister”: that is, in the absence of specific crossdressing laws, crossdressing becomes the alibi for illegal sexual contact. Now, the situation has inverted: in response to the moral panic of this century, trans people in the UK can be prosecuted for sexual assault for not disclosing their trans status. Daisy May wouldn’t tell the same stories to the papers now, because if she did, and if Joe got angry, he could send her to prison and place her on the Sex Offenders Register for life. To protect Daisy May now, Joe would have to have known all along, and be prepared to admit it.

Some years ago, not overly long into my transition, I went to a Harvest Home dance in Orkney. Harvest Home is the annual autumn celebration held to mark the bringing in of the harvest; the dances are Orkney versions of Scottish country dances. I’ve been going to these dances since the age of 3 and know the steps in my bones, but I get to go less often now, partly because I live in Edinburgh, where the dancing isn’t the same and there’s too many tourists, and partly because not every parish holds them as regularly as they did when I was a child. But this was a true island dance, with most of the 80-strong population packed into the school hall, alongside an international collection of artists, there for a festival, which was my excuse for visiting. Nothing makes me feel more at home than an island dance.

I wore a long, drapey blue top, too short to really be a dress, too long to pass as male. In the set dances, I danced on the women’s side; in pair dances, I mostly danced on the men’s, partly because I know those steps best, and partly because I’m very tall. And partly to keep everyone on their toes. There were a few stares, but no-one said anything, and no-one refused to dance with me. I’d always been an oddball, after all. Taking a breather, I chatted with a woman who babysat me as a child; she, a member of the Brethren, a conservative Christian group, wasn’t dancing, though it was quite some concession to even be at a dance. I was halfway to who I am now, halfway doing something to be accepted by my home, halfway bringing something trans into the tradition, and, like and unlike Joe and Daisy May, following the same steps, I was dancing.

You can read the original newspaper stories here, along with a copy of the marriage certificate. I recommend it. If anyone has ideas of how to conduct further research into Daisy May’s life – "Where could we look for records of her name? Is there a music hall archive that might contain evidence of her performances? What was her social milieu? – or knows of commentary I’ve missed, I’d be grateful to hear from you.

What I’m Doing

I’m working extremely hard to make the inaugural Fife Queer Zine Fest happen on Saturday 21st February. It’ll be a celebration of rural and small town Scottish queer culture, with a wee market, a reading room, talks and workshops.

I’ve also kicked off work on a Scots translation of Catullus 63 for an experimental audio project. If you’re a classicist who can explain galliambic metre to me, or a transfeminine person who can speak Latin, get in touch!

What I’ve Read

Noreen Masud’s A Flat Place made me think harder about why I go to high places, and it was unusually good to see my home in someone else’s eyes.

Maria Reva’s Endling is a perfect construction that allows itself necessary fracture.

Janice Galloway’s Foreign Parts reminded me why I tell everyone I can to read her (and, of course, because it’s Scottish fiction of the 90s, a trans woman appears briefly in the early pages).

Incredible archival work pulling Daisy May's story from single brief mentions. The layered analysis about what storyshe needed to tell versuss what might have been true feels crucial for understanding historical queer survival. When I read about Joe never marrying again it hit me how much these silences tell us abou both people in the relationship.

Always love your posts but this one especially ❤️❤️❤️