This is my final essay on the now-obscure Celtic Twilight writers William Sharp and Fiona Macleod. It stands alone as an essay about fixation and authenticity, but will probably be more satisfying if you’ve read some of the other installments: on their gender expression, on the name Fiona, on their weird ideas about Celts, and on the surprising extent of their cultural influence. This essay is about why I’m obsessed.

In Shola von Reinhold’s novel LOTE, the protagonist lives through “transfixions”. She is drawn to historical cultural figures, losing hours and days in research about their lives, days and weeks in hallucinatory reveries in which she is possessed by them. Transfixions are sensuous experiences, offering both “obsessive, whirlwind nights” and “enveloping morphine soaks”. Queer aristocrats, Black artists, and mytho-historical figures — “Jeanne Duval, Roberte Horth, Luisa Casati, Josephine Baker, Nancy Cunard, Richard Bruce Nugent, Luwig II Bavaria, Bel-Shalti Nannar” — haunt and guide her life, offering escapes from the tedium of daily oppressions. Transfixion is the neccesary “feeling not only of recognising, but having been recognised.” Shola writes more clearly than anyone else I know about the way that researching, writing and dreaming other lives can transform one’s own life. I love her word for this process, because I too am transfixed.

Wilfion — the non-binary soul of whom William Sharp and Fiona Macleod were, in their own understanding, the two complementary expressions — has been with me for some five years now, more abiding than any other transfixion. For five years, whenever I’ve heard the name Fiona, I’ve gripped the speaker’s arm and said, “Can I tell you a story?” In the middle of unrelated conversations, I’ve been unable to stop the words spilling out of my mouth: “Have you heard about the time when Tennessee Williams’ lover channelled the spirit of a Scottish Celticist who was also the inspiration for a proto-communist opera at the original Glastonbury Festival?” I leap from connection to connection and my friend’s eyes turn glassy. I’ll protest, “I swear it’s true!” But while the facts are true, my obsession is more of a dream.

I can be ambushed by Wilfion at any moment. I see a talk about Patrick Geddes’ influence on town planning in Edinburgh, and walk the streets thinking about how Geddes was Fiona Macleod’s first publisher. I’ll see the latest H.P. Lovecraft adaptation and wonder whether they’ll use the same garbled Gaelic as the author, without knowing from what pirate they’re pirating. I’ll write about the use of trans figures in the literature of Scottish devolution and have to persuade my editor that, yes, this digression about “the dream-lady from Iona” in G. Gregory Smith’s original essay on the Caledonioan Antisyzygy is essential to my purpose. I’ve adapted their life for BBC Radio and spoken about their language for a special podcast double episode. I’m 12,000 words in to an unpaid essay series in a maddening effort to let them go, and their grip on my mind has only become tighter. Why can’t I stop thinking about them?

I think the answer lies in the way in which Wilfion was a fantasy to themself. When William Sharp was revealed as “the author (in the literal and literary sense) of all written under the name of Fiona Macleod,” commenters remarked on the extraordinary incongruity of the gender expression. William Sharp was a robust, handsome man with a luscious beard, while Fiona Macleod had drifted ethereally out of a George William Russell painting. Macleod proclaimed herself the child of Romance and Dream, while Sharp travelled around Europe starting magazines and negotiating book contracts. She was his necessary wish, and he was her necessary vessel. Both Sharps, William and his wife Elizabeth, wrote about how essential Fiona was, how her existence could not be denied, how she enabled a crucial part of Wilfion to live — and yet, as far as we know, William never allowed her to become flesh. Her one earthly appearance was in the body of his lover, showing herself as a fraud, a joke or a favour to an admiring patron. Fiona Macleod existed only in words, and only for a decade, but she burned very brightly for those years, the same years in which physical and mental illness broke down the body that carried her.

Against these fantasies, I’ve asserted in these essays a few realities. I’ve contrasted, for example, Fiona’s appropriative ethnic claims and terrible Gaelic with the truth of a living language and a land-based political resistance. I’ve contrasted Fiona’s textual sex with my own medically-assisted transsexuality, the changes I’ve made to inhabit the womanhood that matters to me. Such binaries, though, do a disservice to the complexity of life as it’s really lived, in which fantasy animates reality and the breathing stuff of life is as much dreaming as awake. That is, when Màiri Mhòr was singing of bloody land war in Skye, she was also deploying a fantasy, however well-rooted, of what it mens to be a Gael, and when I change my body I do so in service to what I’ve read in 500 trans novels and books of gender theory.

My first poetry collection, Tonguit, has one of my earliest Scots poems, ‘Visa Wedding’. It begins, “Listen, hid’s semple: in Orkney A’m English; in England Ah’m Scottish; in Scotland, Orcadian”. Fifteen years or so after I wrote it, that remains my clearest explanation of my own cultural identity. Brought up in Orkney to English parents, people in each place I’ve lived see a different origin in me. Even now, when I perform in England I’m usually introduced as Scottish, and when I perform in Scotland I’m usually introduced as Orcadian. But when I travel oversees something else happens: now I’m from nowhere at all, but rather from other people’s fantasies of what Scotland is. To Americans, in the poem, “tursit in that muckle myndin an mad-on ancestry”, I can become a “kiltie mascot”, for all I’ve never worn a kilt and grew up listening to the island dance band playing ‘Blanket on the Ground’. Now, when I travel with my verse novel in the Orkney language, people want to know, “Is the language real? Do people still speak it? Is it authentic?” Of course it isn’t. Which is to say, I spent five years working to make every word in it as true to the language I grew up with as I could. Which is to say, it’s as authentic as anything else.

After Macpherson’s Ossian, the Scottish Gàidhealtachd came to European and American readers to stand in for authenticity itself, a land of masculine values, epic landscapes and romantic quests, an authenticity which was all the more authentic for being lost to time. Subaltern authenticity is the fantasy of conquerors. Scotland still plays this role for hikers of the West Highland Way and the children of settler-colonists returning to a dream of roots. Scotland still plays this role to itself, a country that is and isn’t, and I’m yet to meet a Scottish writer who isn’t wracked by whether or not they’re Scottish enough. Every Gaelic and Scots writer I’ve met is likewise doubtful about whether they’re doing the language right. Still and on, that doesn’t mean just anyone can edit Scots Wikipedia – though if I were pressed to explain why, I’d tie myself in linguistic knots no less garbled. Those who long for authenticity don’t have it, and those who have it doubt it.

I’m drawn, then, to someone whose pursuit of authenticity led them into the parodically inauthentic. Every Scottish writer fears being exposed as William Sharp, as someone whose national literary dreams float free of the good earth, and so does every transsexual. I’m writing rhapsodically about a fool whose claim on womanhood was no more or less than a thin thread of fantasy at precisely the time when every national newspaper is pleased to call me deluded. Against such depredations, it’s tempting and perhaps necessary to make constant assertions of reality: Womanhood is my lived experience. It’s the way God made me. It’s the law (it was the law). Trans people have always been here. Have you read this study about the trans gene? Have you read this Marxist essay on how trans women belong in the sex class of womanhood? We make pantheons of trans historical ideals who belong to different gender regimes, slideshows of trans trailblazers who never used the word “trans”, listicles of trans authors who only wanted to write about the world.

William Sharp and Fiona Macleod do not belong on any such list. They’re terrible trans role models, as fake as they come. I’m drawn to them like I’m drawn to Irene Clyde, the sex negative gender abolitionist who also authored the international legal case for Imperial Japan’s invasion of Manchuria, or like I’m drawn to François Timoléon, abbé de Choisy, who lived for years as a woman and had infuriating amounts of hot trans sex, or perhaps only wished that he had. “We want [de Choisy’s memoir] to be true because it is so fantastical. But if you regard it with any scrutiny, there are implausibilities, contradictions, anachronisms and no contemporary corroboration whatsoever,” said Paul Scott, a killjoy. I think we learn more about the history of trans life from figures who are worrying and incomprehensible to trans life now than we do from any potted biography of a political hero. Similarly, we learn more about Scotland by studying its weirdest expressions. If we can look at our inauthentic origins and find them true, we are better able to live as the contradictions we are.

A transfixion, then, is someone whose life is so impossible that it makes yours possible. When you find your transfixion in a historical footnote, she rewrites the whole book. You lean closer in to the oil painting and wonder, is that him, between those two faces, shrouded in light, a pair of eyes, looking back at you? As you follow your transfixion’s trail, you can hardly believe how many traces they’ve left, when no-one else seems to have followed this trail before. Who hid all this from you? Why do they want you to believe you’re only dreaming, as if an act as expansive as dreaming could ever be only? In LOTE, the protagonist follows her transfixion to a residency where the cleverest and most boring artists in the world try to reason away her very ability to be transfixed. I’ll let you follow that novel where it goes: please read it.

I’m tidying away my Wilfion papers, with both grief and relief. William Sharp and Fiona Macleod have, for now, as led me as far down the garden path as they can. They’ll retreat into the mists, where Margo Williams and Konrad Hopkins also found them, making a space for another spirit to appear. I’m ready to be transfixed anew.

What I’ve Made

I climbed up my hundredth mountain.

My short story Aince, written as a schools resource for Scots Hoose, has been republished in the anthology The Wheesht, which is available for free. Aince is the title story of my book of fables, which is very nearly done — in fact I’m supposed to be working on it right now.

What I’m Doing

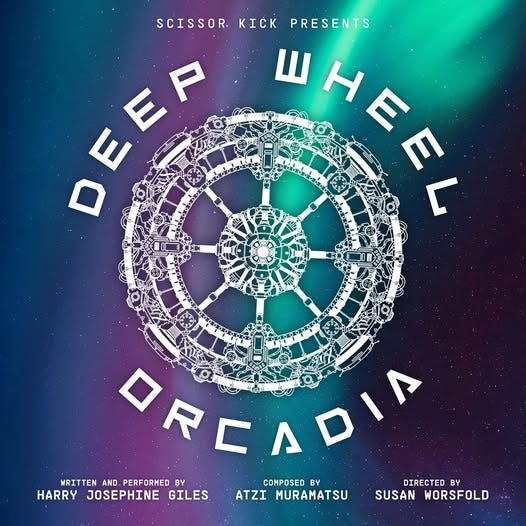

This summer, I’m touring the full stage show of Deep Wheel Orcadia, an Orkney language story in poems with a full score performed live y string quartet. Tickets available here.

26th June 2025: St Magnus International Festival, Orkney

18th + 19th July 2025: The Lemon Tree, Aberdeen

25th + 26th July 2025: Eden Court, Inverness

What I’m Reading

Ella Frears’ Goodlord does my favourite thing poetry can do: it’s open and clear in its style, while twisting and complicating everything it speaks about.

Rivers Solomon’s Model Home writes madly from a place of madness: Solomon is a writer who demands readers stay present to their horror.

Jeanne Thornton’s A/S/L is the book I’m pressing into everyone’s hands and demanding they read. If you were ever queer and alone on the early internet, it’s for you.

I keep thinking about Borges saying that someone who lives in the desert is less likely to write about camels, because camels are just another part of the world to them and not a signifier of difference— I suppose for me the distinction comes from the outsider focusing on the things that are different to the outside, while the insider sees them in a more surprising way.

I also keep thinking of Jan Morris talking about Venice being transformed into the image of itself as it depends more and more on tourism; that sense of the image destroying the world it gave the appearance of showing? I think this is because I also grew up in the north of Scotland, so everyone’s image of “Scotland” seems strange and unknown to me

I'm new here and intrigued. I need to learn more!