Here’s a nasty little game my mind likes to play: if I were to die in an accident tomorrow, what, as my life replayed in those final moments, would I regret spending my time doing? The game bears no relation to my actual experience of nearly dying – twenty years ago, knocked down by a wave, pulled into deep waters by a rip tide, smashed against coral – which was, through the pain and confusion, remarkably calm. “Oh,” I thought. “That’s all I get? That’s a bit disappointing.” And then I thought it was funny that I was thinking that, and then I blacked out. A lucky wave, I’m told, pushed me closer to the shore, where stronger swimmers carried me out of the water and back into a life neither more nor less profound for the experience.

What are you doing that’s a waste of time? The question is clearly not about dying but rather about living. It’s an expression of anxiety and guilt, the mind’s ceaseless observation of internal and external landscapes to try to spot what might be wrong. The answer to the question, then, says more about what I’m currently afraid of than what is truly valuable in my existence. Nevertheless, I do know the answer. It’s spending a decade on Twitter.

I left Twitter, and all other social media – my Facebook having long since degraded into watching arguments from a distance, my Instagram already deleted from my phone for showing me too many beautiful people – two years ago, more or less cold. I had built a following of 12,000 ( impressive from one perspective and desultory from another); the skill of compressing thought into shallow space; a network of play, discovery and expression; an unreadable life journal; my own personal hate group; and a mind-altering addiction. There were only so many times I could say the word “hellsite” before doing something about it. I decided to take a month off, and at the end of the month I could find no reason to log back on. I’ve kept the accounts to post occasional adverts for my events, the algorithms showing them to fewer and fewer followers each time, but I’ve never again been drawn back in to scrolling, replying, posting, there or anywhere else. And I am, as so many of us say we are, as so many of us cannot help but keep saying, happier for it.

But before getting to the regret, before punishing myself a little more for my time generating value and attention for a billionaire technofascist to capture, before adding to the chorus of It’s the phones!, before counting the harms, I want to remember what I miss from Twitter. What I do not regret.

I miss the jokes. 20th September 2015, the day we learned the pig story about former Prime Minister and architect of mass death David Cameron, is the day I laughed the most in my entire life. Even now, every time I think about it, I smile. I miss learning about the news from a range of radical perspectives, and am frightened about what learning about them instead from liberal news outlets has done to my understanding. My boifriend and I have taken to saying, “Yes, I read that Guardian article too,” and then making expressions of horror at each other. I miss the art we made before Musk killed the bots. I miss the occasional well-paying job I would get by pushing myself in people’s faces day after day, reminding people, some of whom had commissioning budgets, that I, an interesting person, existed. I miss sharing ideas with a broad network of curious, intelligent people. I miss knowing a lot of people a little. I miss knowing what’s going on. The protests, the parties, the gigs, the general sense of being plugged in to a smart milieu. No matter how much I tell my friends that they have to text me if they want me to know about something, I still find myself on an island of ignorance. I was lonely online, and now I’m lonely in a different way.

I am glad for all these things, especially the money. I am not glad for how often I was drawn into arguments. Arguments with complete strangers to whom I gave the power to make me feel terrible about myself; arguments with former friends and colleagues whom, distanced by two screens and the hidden infrastructure of late capitalism, I failed to treat as human, or who failed to treat me as human. I am not glad for the hours I scrolling from horror I could not address to horror I could not address, the times I would get so distracted by some new indignity that I would miss my train, or a phone call from my lover, or the bird landing on the windowsill. I am not glad of how often I was activated by a new injustice, compelled to make a political commitment I could not keep, nor how much social media demobilised me. My years of most involved direct action were the years before I had a Twitter account and a snitch in my pocket. I am not glad for how much time I spent on one website, generating profit for a private company, contributing to a social network that was always, obviously, inevitably, going to be used to drastically advance the cause of 21st century fascism. How much time? I am frightened to make an estimate. I could have written a whole other book. Books. Instead, I gave my words freely to bosses who did not deserve them and will not remember them.

And I am not glad of how the website rewired my brain, making the kind of concentration and deep flow that was natural to me as a child into a precious resource I am only just beginning to renew. My mind now feels like an exhausted, over-cultivated soil, finally let fallow, its seed bank pushing up a few tentative stems.

What did I do, once I left? I took up crosswords. Whenever I was tempted to reach for my phone and the timeline, I did a crossword instead, giving that dopamine-seeking neuronal network some form of the hit it craved. I read more books. I worked on knowing fewer people better, loving more deeply. I also, without even realising that I was fulfilling a promise made by a hundred time-to-quit-Twitter blogs, learned a whole new language. I felt lonely. I felt disconnected. I felt free.

This public diary, then, is an attempt to regain some of what I enjoyed about Twitter without mowing down the meadow I’ve regrown. I benefit from a commitment and a deadline, so I aim to post two short pieces a month on this mailing list about whatever it is I’m thinking about at present. I hope to use this space to do some of the thinking-in-public I did on Twitter, and to write about what I care about a little more deeply. I hope I’ll reconnect with people I met there, maintaining a few more of the light relationships that are part of a rich social world. I hope, also, to advertise to you: I’ll include notice of upcoming events and recent publications, as below. Some of this will change as I write.

What have you been doing since we last spoke? And where are you going now?

Recent Projects

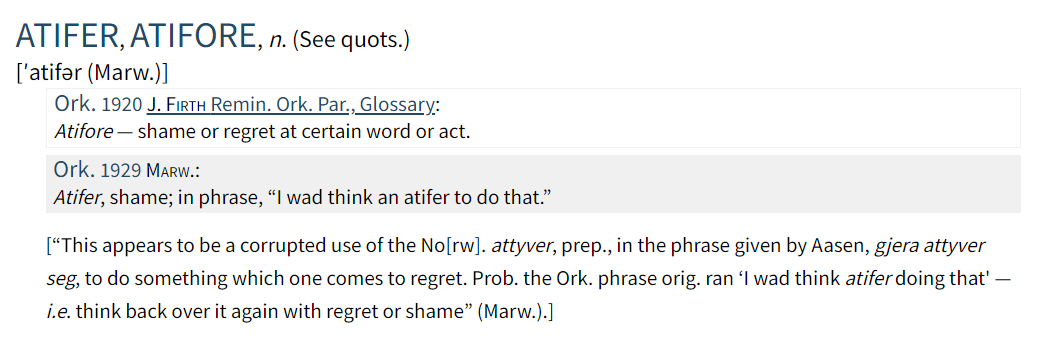

In November 2024, with the musician Malin Lewis and supported by the Edinburgh Futures Institute, I launched Unco: A Queer Scots Lexicon. It’s the culmination of years of work on queerness in the Scots language, which you can also hear me talk about on The Allusionist podcast. The publication is available for free and we’ll be touring the performance in 2025.

I featured in Alistair Heather’s documentary on Scots language poetry for BBC Radio 4, Beyond Burns.

Upcoming Events

On February 20th I’ll be reading at the launch of Gutter Magazine 31, with a new short story from a collection of fables I’m developing.

What I’m Reading

Greasepaint by Hannah Leverne is a boisterous portrayal of 1950s butch bar culture and Jewish anarchism. I was carried along on the fierce wave of its poetry, delighted by its commitment to sonic joy, and pleased to encounter queer masculinities that were neither apologetic not idealised.

Earthbound Orkney by Rebecca Little and Tom Morton is an essay about building and making with earth, and about the art of daily life. Taking Neolithic artefacts as a starting point, it documents a project to make compressed soil cubes and polished earth balls of astonishing beauty. It brings truth to the term “labour of love”: it’s a book about loving the working of earth.

Lost People by Margaret Elphinstone is a postapocalyptic parable by one of Scotland’s greatest living writers. Elphinstone is known for historical novels of huge scope, but distils her perennial theme – the life of communities in precarious settings – into a short tale of perfect clarity. A book for gardeners of every kind.