On Wilfion and the search for trans stories

William Sharp and Fiona Macleod, Part One

This is the first of a series of pieces about the Scottish writers William Sharp and Fiona Macleod. I’ve been obsessed with them for years, often finding myself – usually when I’m supposed to be doing something else – losing hours in the archive trying to make sense of their story. Reading Sharp and Macleod, in the fullness of their flawed romance, uncovers forgotten foundations of contemporary literature and unsettles easy assumptions about minority history. At times, for all that they’re now rarely read, I’ve felt that it’s impossible to understand contemporary Scottish writing without understanding Sharp and Macleod.

This first piece will outline their story and think about it from a trans perspective. Future pieces will investigate the origins of Fiona’s self-naming, the Celtic Twilight and ethnic masquerade, and the way Sharp and Macleod’s ghosts continue to haunt both Scottish and international culture.

I’m proud of this work and have wanted to do it for a long time. If you like it, I’d be very grateful if you’d share it with one other person who’d enjoy it.

In late December of 1905, friends of William Sharp, including the Irish writers W.B. Yeats and Æ (George William Russell), received a posthumous letter sent by Sharp’s wife, Elizabeth. It read, in part:

This will reach you after my death. You will think I have deceived you about Fiona Macleod. But, in absolute privacy, I tell you that I have not, however in certain details I have (inevitably) misled you. Only, it is a mystery. Perhaps you will intuitively understand, or may come to understand. “The rest is silence.” Farewell.

William Sharp, born in Paisley to a middle-class Protestant family and educated in Glasgow, was a prolific figure of fin-de-siècle British literature, entangled with the Pre-Raphaelite and Neo-Pagan movements of the late Victorian period. As an energetic jobbing writer, from 1882 on he wrote biographies of Rossetti, Shelley and Browning, published multiple volumes of poetry and adventure tales, and created the single 1892 issue of The Pagan Review under around ten different pseudonyms. He worked with the Edinburgh polymath Patrick Geddes in the The Evergreen magazine’s circle of ecologists and revivalists, and was a member of the London chapter of magic’s most infamous secret society, the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. Wherever new ideas about mysticism and the environment could be found, he was there.

Reading Sharp’s letters and biographies, he reminds me of people I’ve met often in the Highlands and Islands: wandering souls gripped by a spiritual passion for nature, always seeking some new idea, or new imagining of an old idea, which could heal the cracks in their own mind and the cracks in the world. Sometimes they buy a croft on an outlying island with grand ideas about permaculture, then leave after the first hard winter. Sometimes they stick it out and become central to the local community, running thronging weekly tea mornings and the more poorly-attended art workshops. If Sharp lived now, he would look you deep in the eyes and talk about microplastics and selkies and how the moonrise at Calanais is the world’s most sacred experience. He would not be terribly wrong. He would not be terribly unlike me.

Fiona Macleod was a younger contemporary of Sharp, working in the same circles. Her literary career began a decade later, in 1894, with the novel Pharais: A Romance of the Isles, followed in the following decade by an extraordinary profusion of work: further novels, anthologies of folklore and short fiction, collections of poetry and nature writing, and literary essays on Celtic culture. She was celebrated as a leading light of the Celtic Revival – not entirely through her own efforts of self-promotion – and as its leading female and Scottish proponent. By all accounts, her work, which portrayed a Romantic and spiritual view of Gaelic culture, featuring many doomed lovers and rhapsodic descriptions of wooded glens, was an enormous popular success – to such a degree that people began (as I’ll explore in the next piece) calling their children Fiona. In 1896, the Aberdeen Free Press wrote that “We know of no author since Sir Walter Scott that has been so eminently successful as Miss Fiona Macleod”. The Irish Independent called her “the most remarkable figure in the Scottish-Celtic Renascence” and her work “another triumph for the Celtic genius”.

Indeed, she was by all accounts a Celt from birth: a native of the Inner Hebrides, perhaps Iona, from an old Catholic family, and a fluent Gaelic speaker. Her short fiction and folklore often includes the framing device of being deep in Gaelic conversation with an old bodach or cailleach walking along a wind-blasted shore, who shares with her deep native wisdom. She wrote letters to fans and friends across the world, and engaged in intense debates on the role of literature in the Celtic Revival. Much to the consternation of her Irish nationalist correspondents, she took – as I’ll discuss in more detail in a later post – a position more or less against Irish independence, Gaelic-language writing, and separatist approaches in general, speaking instead for the infusion of a Celtic spirit into the British project. Fully subscribed to racist anthropological theories, she wrote, “The Celt falls, but his spirit rises in the heart and the brain of the Anglo-Celtic peoples, with whom are the destinies of the generations to come.” All she wrote, she wrote as a native Gael passionate about the culture of her people, and her readers read her as a much-needed authentic representative of Gaelic life.

Of course, she was nothing of the kind. She was William Sharp. The postscript to the letter, written after the signature, as if Sharp had only just remembered his purpose for writing, read: “It is only right, however, to add that I, and I only, am the author (in the literal and literary sense) of all written under the name of Fiona Macleod.” Two weeks earlier, on the 15th of December, newspapers across the country and internationally carried a notice written by Richard Whiteing that William Sharp was dead and had been the author behind Fiona Macleod.

In truth, many had already suspected. The revelation of Fiona Macleod’s identity was spoken about in the New York Times as resolving “the most interesting literary mystery in the United Kingdom”, though other articles wrote that the truth has long been suspected. Many other candidates were proposed – Elizabeth Sharp; some unnamed cousin; the scholar and Gaelic-language advocate Ella Carmichael (who said in response, “As if I would make out Highlanders to be such soft-brained lunatics!”) – but Sharp’s name was always to the fore. Their literary projects, and their movements across Europe, had been too closely connected. Macleod wrote denials to her correspondents; Sharp threatened legal action; Sharp dictated Macleod’s letters to a female relative so as to maintain different handwriting for the two authors; but the rumours had always persisted. In the years following, the public coverage of Macleod’s writing, although it still had defenders, began to sour under the authenticity question. More began to notice what Gaelic speakers had long been saying, that Fiona Macleod’s work bore little resemblance to contemporary Highland life, and that her Gaelic itself was garbled. Why had Sharp persisted so long in this practise? In what way was this not a deceit? What would we come to understand?

In 1910, not so very long after their death, Elizabeth Sharp published a memoir of the entwined lives of William and Fiona, giving each their containing personal reminiscences and many long extracts from their letters. Although it is very clearly a defense of what many now saw as a literary fraud, and so should be understood as partial and purposeful, the memoir does share William’s and Fiona’s own ideas about what was going on in their lives. From this material, it’s clear that Fiona was more than a pose for William, more than a convenient mask behind which he could speak his ideas about Celticism. He wrote:

This rapt sense of oneness with nature, this cosmic ecstasy and elation, this wayfaring along the extreme verges of the common world, all this is so wrought up with the romance of life, that I could not bring myself to expression by my outer self, insistent and tyrannical as that need is. [...] My truest self, the self who is below all other selves, and my most intimate life and joys and sufferings, thoughts, emotions and dreams, must find expression, yet I cannot, save in this hidden way.

Fiona fulfilled an emotional need for William, one which he otherwise struggled to express. As the Fiona work continued, she began to take a stronger hold over William’s life. In one letter, they say that “More and more absolutely, in one sense, are W. S. and F. M. becoming two persons—often married in mind and one nature, but often absolutely distinct.” This letter was signed as “Wilfion”, a name given to them by Elizabeth as a description of a third essential personality which lay beneath William and Fiona. Elizabeth wrote:

In surveying the dual life as a whole I have seen how, from the early partially realised twin-ship, ‘W. S.’ was the first to go adventuring and find himself, while his twin, ‘F. M.,’ remained passive, or a separate self. When ‘she’ awoke to active consciousness ‘she’ became the deeper, the more impelling, the more essential factor. By reason of this severance, and of the acute conflict that at times resulted therefrom, the flaming of the dual life became so fierce that ‘Wilfion’—as I named the inner and third Self that lay behind that dual expression—realised the imperativeness of gaining control over his two separated selves and of bringing them into some kind of conscious harmony.

In this account, Fiona is not a lie, because she is a separate personality, an expression of Wilfion’s dual soul. The facts of her life – growing up in the Western Isles, speaking Gaelic, intimacy with the culture – were misleading, but they were a true manifestation of Wilfion’s spirit. The meaning of the work was true.

How should we understand this now? One possibility, tempting to a trans writer, is to understand the epicene Wilfion as non-binary or genderfluid avant la lettre. Diving deep into the letters and reports, we can find plenty of evidence. In 1880, William wrote to a friend, “Don’t despise me when I say that in some things I am more a woman than a man”. In another “I am tempted to believe I am half a woman”. Of being in the mental company of the women in his life and writing as Fiona, he said, “I have never so absolutely felt the woman-soul within me: it was as though in some subtle way the soul of Woman breathed into my brain”. He claimed to Elizabeth that Fiona had been with him “while I was still a child”. An author in the Times Literary Supplement wrote that, “If report speaks true, the urge to ‘be’ Fiona took so strong a hold on him that the handsome, bearded man would put on woman’s clothes when Fiona was going to write.” Is this the truest self which demanded expression? Was the “self who is below all other selves” a woman?

I have not found the rumour reported in the TLS substantiated anywhere else, and it was both published decades later and vigorously refuted by William’s brother-in-law. The quotations about being a woman are expanded as a description of William’s emotionality and commitment to friends. Certainly, he was drawing on sexual theories of the time, which saw all people as combinations of masculine and feminine principles. He also drew on such feminist ideas in his Pagan writing, writing that “The long half-acknowledged, half-denied duel between Man and Woman is to cease [...] through a new recognition of copartnery” (though, sad to say, he went on to oppose the abolition of marriage). Androgynous figures, sometimes through exoticised racial minorities – in one case a “Black Madonna” who is both Mother and Christ – abound in his work; so too do fated lovers who seem to want to become each other, to entwine into one soul. Through one lens, he could not appear more trans; through another, he was just a man who liked talking about feminine spirits. In seeking to find a trans ancestor, we risk simplifying the complexity of Wilfion’s self-identification. On the other hand, to say that there’s nothing trans going on here also seems wilfully denialist.

What, then, about the Mad or neurodiverse lens? Several of their contemporaries interpreted Wilfion as what we would now call a plural system, a group of identities sharing a body. The TLS article makes this exact case, drawing on psychological theories. Yeats himself said:

Fiona Macleod was a secondary personality—as distinct a secondary personality as those one reads about in books of psychical research. At times he (W. S.) was really to all intents and purposes a different being. He would come and sit down by my fireside and talk, and I believe that when ‘Fiona Macleod’ left the house he would have no recollection of what he had been saying to me.

William F. Halloran, their modern biographer, also makes a compelling case that Sharp experienced manic-depression, sometimes caused by and sometimes causing the tension of the William/Fiona split. Elizabeth, in the memoir, writes very clearly and explicitly of his mental health struggles, his depressions and his bouts of extreme productivity.

But Elizabeth also disputes Yeats’ account as spurious, and Yeats, who believed that Wilfion’s separate spirits visited him in dreams, had his own reasons for giving a quasi-psychological, quasi-spiritual account of the split. Morton Prince reported the case of Charlotte Beauchamp in 1906, laying the foundational narrative for what is now called dissociative identity disorder: all these writers would have known the case, and perhaps it influenced their tellings. Later, in an article disputing the authenticity of the Macleod folklore material, the American Hispanist Georgina Goddard King wrote that “The parallel case is not Sally [Charlotte] Beauchamp but Thomas Chatterton”.

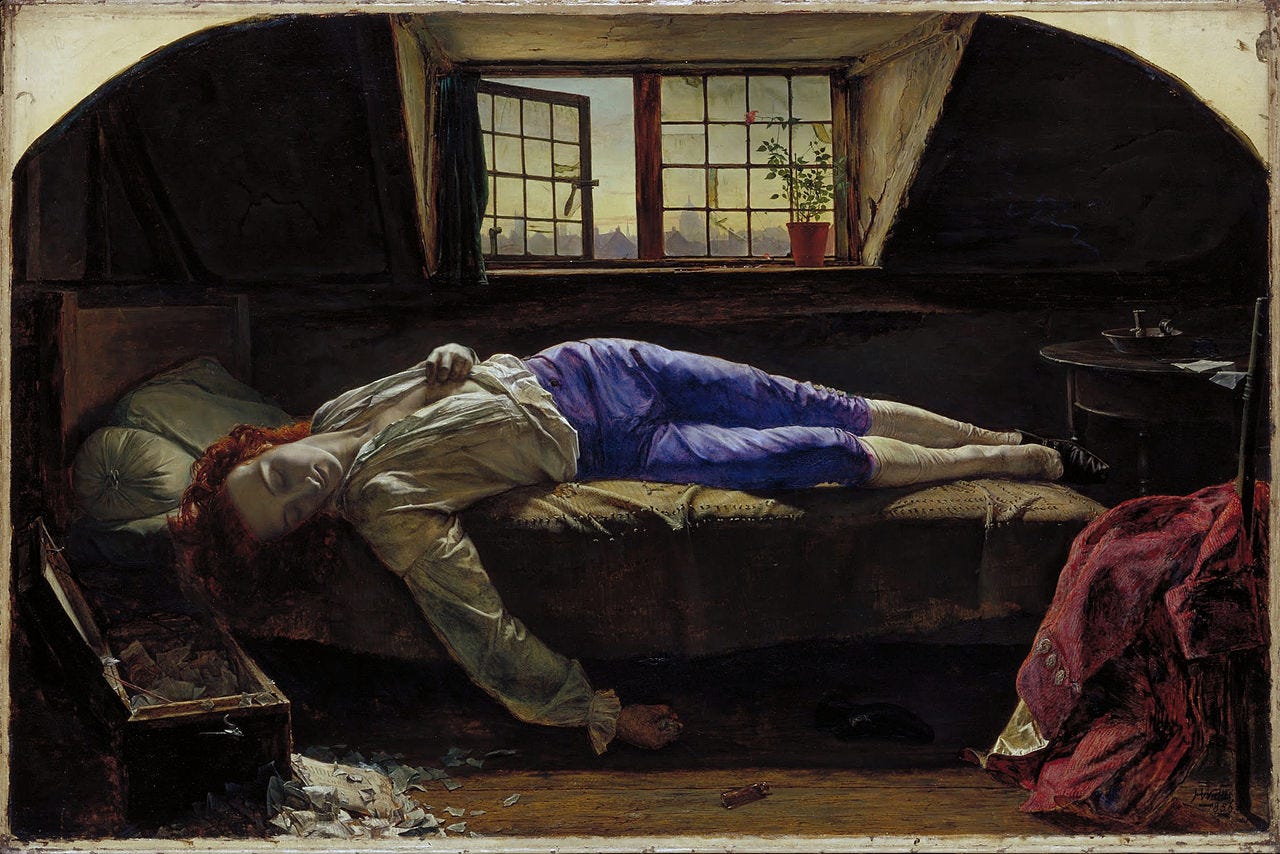

Let’s pull on that thread. Chatterton (born 1752) was a poetic darling of the later Romantics and Pre-Raphaelites, symbolising the beauty and tragedy of the life of imagination. His precocious teenage poetry career began by passing off his work, written in a pastiche Middle English of his own invention, as that of an imaginary 15th century mystic. Throughout his brief flowering, he wrote in voices inspired by or in imitation of others, taking on many personae, including the Ossianic. For later movements which saw themselves as reviving earlier artistic ideals, he was – or was turned into – a perfect symbol. Chatterton committed suicide (or accidentally overdosed on arsenic as a treatment for an STD) at 17.

The scene of Chatterton’s death was later painted by the Pre-Raphaelite Henry Wallis, for which the model was the young George Meredith. Meredith, who became an influential novelist and poet, was also later an admirer of both Sharp and Macleod. He was very struck with Fiona’s writing, and asked for a meeting. Sharp persuaded the writer and editor Edith Wingate Rinder (who was the dedicatee of Pharais; who was perhaps his long-term lover; who was credited as the original inspiration for Fiona Macleod) to impersonate Fiona and visit Meredith. Meredith said that she was “a handsome woman, who would not give me her eyes for awhile”. Yeats claimed that Meredith described the fake Macleod as “the most beautiful woman he ever saw”. The record of this encounter led some correspondents to dispute the eventual revelation of Macleod as Sharp, and it is this debate which prompted the TLS article which claimed that Sharp dressed as a woman. Every thread in this story is knotted around every other thread.

One could make a strong case for either and neither of the trans and Mad readings. Any reading is an attempt to understand the past in the terms of the present. We can do careful scholarly work to try and appreciate how people in the past thought, to try and dispel our own prejudices, but we will always be reading through our own glasses. We will always be seeking to write our own books. Peter Ackroyd’s Chatterton is a fine examination of this essential aspect of reading and writing historical artists. Shola von Reinhold’s LOTE makes a grand case for the importance of being transfixed by them.

For myself, I choose a maximalist approach. All of these understandings have truth, and none of them can be tamed by contemporary categories. The more deeply I read Wilfion, the more illuminating and disturbing by understanding grows. The wilder. I take Wilfion’s own words seriously: they saw themselves as two separate identities living in one body, as expressions of the masculine and feminine principles of an underlying soul, as a unity of opposites. I choose not to understand them in medical terms, but in the spiritual terms they preferred. William saw something of a woman in himself, and out of spiritual necessity found a way to express it. Fiona lived in books and letters, just as many trans women now live in Discords and Substacks. These are forms of transition. William also lived his daily life as a man. Fiona also constructed a racist Celtic fantasy that bore no resemblance to the reality of life in the Gàidhealtachd.

Living with these multiplicities and inauthenticities is, to me, an essential part of living transly – and an essential part of living as a woman. All of us who live women’s lives live in fantasies, fantasies which are shaped by the cultural stories and racial prescriptions of our time (citation: any advert for skincare or cosmetic surgery). And we also live in the stickier material experiences of bras and choromosomes, medical abandonment and social condemnation. In these knots of truth and fiction, where one is not fully extricable from the other, we seek certain grounding authenticities: diagnosis, a plausible history, a DNA test from 53andme, a thorough reading of the feminist theory of women as a sex class, a coming out post, a declarative political position.

The most difficult thing for a contemporary trans writer to come to terms with in this story, is that the two fantasies, writing as a woman and writing as a Gael, are not separable in Wilfion. Those who would condemn us for gender fraud might seize on any story of ethnic fraud as proof of our simple unreality. But I cannot give Wilfion a simple trans or Mad alibi, cannot explain what they did as simply an expression of suppressed gendered longing, cannot (as I might wish to) separate the two fantasies, no more than I can dismiss what really is trans in their story. Would transition have saved her? Fiona didn’t need medical transition when she had the Celtic Twilight. For William, his Celtic spirit was his feminine spirit. In his introduction to his wife Elizabeth’s Lyra Celtica, an anthology of verse from across Celtic cultures, he approvingly quotes Ernest Renan: “No other [than the Celt] has conceived with more delicacy the ideal of woman, nor been more dominated by her. It is a kind of intoxication, a madness, a giddiness.” Sharp’s commitment to beauty is his commitment to a fantasised Celt and to a fantasised femininity. These layers of fantasy are not a simple thing for this contemporary trans woman to accept, but they are part of my cultural history. William believed that he had every right to claim an imagined Gaelic heritage for himself as a spiritual project, because he was Fiona, and Fiona was true.

We can understand, or come to understand, in our own way. As we search for trans histories, we find layers of truth and deceit: the ways we understand ourselves, the ways others understand us. The partiality of the record. One thread of literary imagining tangles around another. We are condemned and defended, remembered and forgotten. Only, it is a mystery. The rest is silence.

Sources and Further Reading

The biographical details are drawn from William Halloran’s and Elizabeth Sharp’s biographies. Letters are from these or the Sharp/Macleod Archive. Moll Heaton-Calloway’s work on their epistolary life is brilliant and helped me a lot. Reviews are quoted in publications by Patrick Geddes and colleagues: I cannot vouch for all their authenticity, though I have tracked down the originals of one or two. I have a screenshot of the TLS article but no longer have access to their archive so can’t give you the date. Duncan Sneddon is my source for the Ella Carmichael quotation: the article is excellent and I’ll discuss it in a later piece. Apologies for the laxness of my sourcing: I hit deadline and am unpaid! I would love to work up this material for a paying source.

If you’re interested in reading Fiona Macleod, the vast majority if not all of her work is available at archive.org. I cannot recommend the novels, unless you’re a fan of spiritualist fantasias and doomed lovers flinging themselves into various Highland waterways. The essays on Celticism are chiefly of historical interest. The poetry has its joys, but often cloys: at its best, it reads like Gerard Manley Hopkins with rather less skill and discipline. For the folklore, you’re far better off going to a reliable source such as Iain Òg Ìle, though her versions are lush and strange for all that they’re confected. The nature writing, however, I think is wonderful, and deserves to be better remembered. The Silence of Amor is a strange, beautiful, elliptical text of love in the landscape, and When The Forest Murmurs is a rich and scholarly (if occasionally spurious) exploration of the intertwining of folklore, history and ecology which clearly prefigures later Scottish nature writers like Nan Shepherd and Jim Crumley.

If you’d like more of my own work on the subject, I fictionalised Wilfion’s story for BBC Radio’s The Poet and the Echo, and revised and expanded the story for Scratch Books’ anthology. I also contributed extensively to the two-part Allusionist podcast on Sharp and Macleod, alongside Moll Heaton-Calloway.

My deep thanks to Jim Rogers, Keava McMillan and the team at Lavender Menace for inviting me to speak on Wilfion and reawakening my obsession. Darcy Leigh helped me think through the intersection of gender and race, and Evan Birnholz helped me with the NYT archive.

What I’m Doing

On March 15th and 16th I’ll be at StAnza Poetry Festival in St Andrews, with a sound poetry event and a poetry zine workshop.

On March 30th I’ll be reading with other trans writers at Argonaut Books, Edinburgh.

I’ve made a bluesky account if you’d like to follow me there.

Have just come across this - What a brilliant piece! And such an interesting story too. Thanks for being so generous with all your archival research x