Some time ago, at the irreverent and chaotic literary night ‘Poets Against Humanity’, an old friend introduced me as “a poet who has almost, but not quite, won several major literary awards”. It remains my favourite of any introduction I’ve ever had. It was bebetter than when the host says a generic line and flubs a pronoun (embarrassing), better than when the host reads out my self-authored bio (excruciating), better than when the host praises me in their own terms (torturous), because it cut straight to something that was very true about me. The host had named the overachiever’s deepest anxiety: that she’ll always be good and never good enough, and made everyone laugh about it together. Unfortunately, a couple of years later, I won a major literary award.

Since then I’ve found myself saying words like “legacy” and expressing the desire to be read after I’m dead. It’s true: I’m ambitious. I’ve set out to do something significant with my primary language of literature, Scots, and for that work to last. I’ve also set out to make a path for other trans women writers in Scotland, of whom there are very few published. I’m now in the extraordinary position, at 38, of my books already being taught on multiple mainstream University courses in my home country. What blessings! Undergraduates and PhD students are writing essays on my work. This means two things: that I’ve had a very lucky start in getting to have a literary legacy, and that that legacy is already out of my hands. I shared some words with the world, and now the world can make of me a ghost.

Fiona Macleod and William Sharp, the two personalities of the author about whom I’ve now been writing for ten thousand words, wanted to have a legacy. In Part Three, we learned about their ideas for the role of Celticism in the British cultural project and in mankind’s spiritual growth. In Part Two, we saw how they created the very name Fiona, and how that escaped their control. And in Part One, I found in them an uncomfortable trans forebear in Scottish literature. Now I want to look at what other artists have made of their work, and how their ideas, in a way far beyond what they imagined, continue to haunt culture.

Fiona Macleod’s first interpretation beyond her own writing was in classical music. Her romantic and visionary form of Celticism inspired composers with similar interests (and to be clear if you have not read the previous essays, the term “Celticist” usually refers to Anglophone artists outwith the Gàidhealtachdan who become fascinated with Celtic cultures for their own peculiar reasons). Her poems, with their strong rhythms, rich assonance, allusive style and overwrought imagery, were well-suited to the operatic style. One of her earliest and most consistent interpreters was Arnold Bax, whose 1904 Celtic Song Cycle was made before her death. Whether she ever heard it I cannot say: there is no mention in her letters that I’ve found. Most of Macleod’s interpreters are English and American, and more than one – like Frederick Delius and Helen Hopekirk – moved back and forth across the Atlantic. She seemed particularly popular with composers who claimed some form of Scottish connection or ancestry, and making lieder of her poetry was fashionable for two or three decades. There’s one Sibelius lied attributed to Macleod, though I can find no source for the text in her work. Even Samuel Barber gave it a go. Most of these interpretations are musically faithful to Macleod’s poetic style: preoccupied with longing for lost loves and lost places.

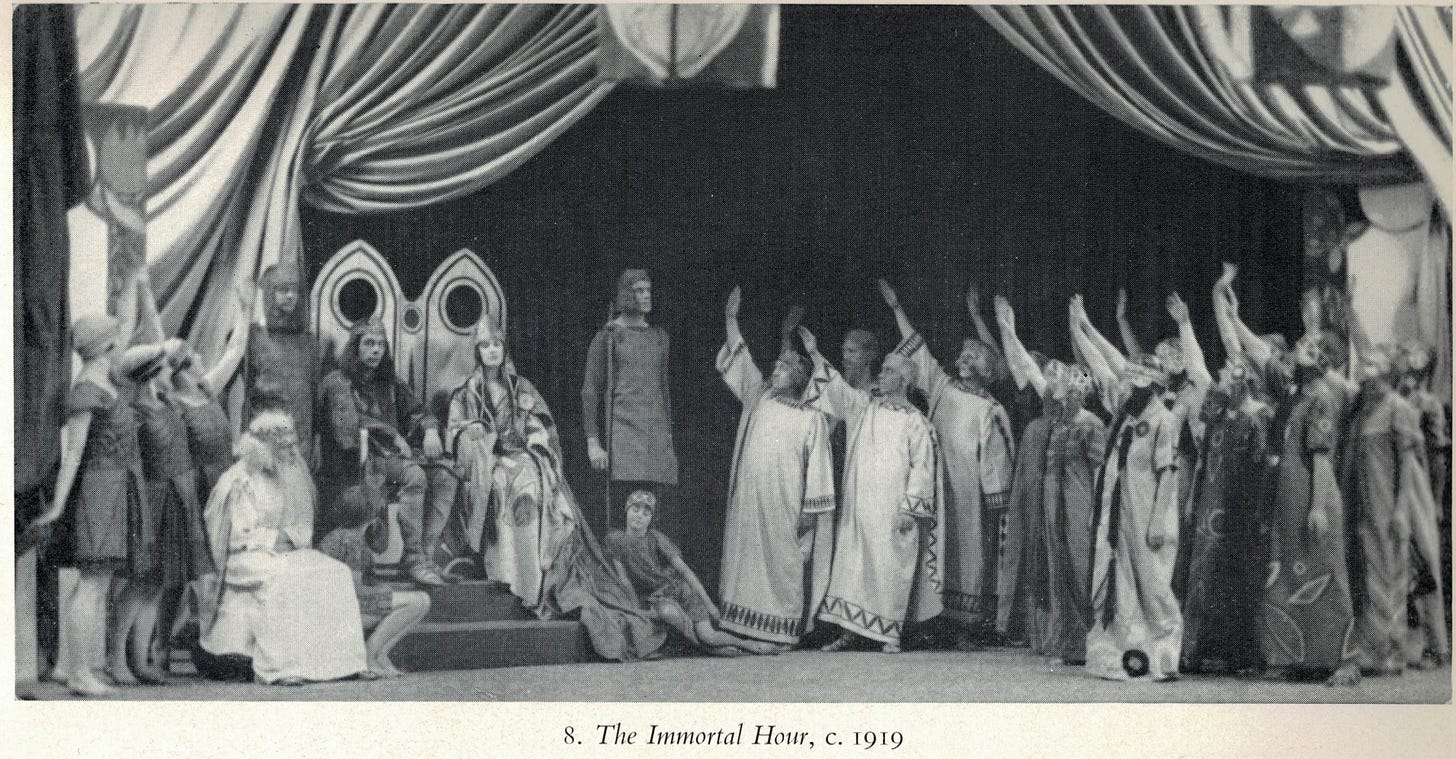

The most famous and successful version of her work, however, goes a step further. The English communist composer Rutland Boughton adapted her brief, fantastical play The Immortal Hour as a full opera for the original Glastonbury Festival in 1914. It is a story of manipulative, godlike Celtic spirits and obsessive, doomed love, a sort of Celticist Rusalka. For Boughton, it was part of a continuous construction of national mythology in popular opera, which he pursued through both Macleod’s ersatz Highlands and Arthurian myth. For him, this national musical project became part of his politics as a member of the Communist Party of Great Britain, which brought both him and the festival into disrepute. In the later Avalon, for example the Lady of the Lake foretells a red star shining in the east that will bring about a new future.

The Immortal Hour was the centrepiece of the festival’s launch. Boughton and his librettist Lawrence Buckley imagined a musical summer school, annual festival and year-round aritsts’ community that would foster a national cultural revival. They chose Glastonbury for its Arthurian connections and growing utopian spiritual reputation. The festival was suppored by Edward Elgar, George Bernard Shaw, and Clark’s shoemakers, a Quaker business founded nearby. The declaration of war disrupted the festival, but the first performance went ahead. It took until 1922 for The Immortal Hour’s London debut. It ran in the capital for 376 performances and transferred to New York.

In 1926, the reaction to Boughton’s communism brought down the festival. His 1915 Nativity opera Bethlehem was revived in London, but the General Strike was underway and Boughton wanted to show solidarity. In the staging, Jesus was born in a miner’s cottage, Herod wore a top hat and tails, and the Roman soldiers wore British police uniforms. The festival’s ruling class backers couldn’t stand it, and withdrew their financial support. Boughton continued composing, but his music became more and more neglected. In 1949, Ralph Vaughan Williams said that “In any other country, such a work as The Immortal Hour would have been in the repertoire years ago”. Though the opera has been revived occasionally since, like Macleod herself, Boughton’s influence and fame have been pushed from British national consciousness. The vision of a socialist musical Avalon at Glastonbury managed by England’s classical music luminaries has likewise given way to the world’s largest greenfield festival, donating most of its profits to various charities, now in partnership with Vodafone.

In 1924, in the centre of a 20-year career in horror writing, while The Immortal Hour was playing in New York, H.P. Lovecraft published The Rats in the Walls. In the story, an American named Delapore returns to his family home in the south of England, only to discover that generations of his ancestors have been maintaining an underground city as a source of human flesh to eat. At the revelation, Delapore is driven mad and begins eating his companion. While he eats, he speaks:

Curse you, Thornton, I’ll teach you to faint at what my family do! … ’Sblood, thou stinkard, I’ll learn ye how to gust … wolde ye swynke me thilke wys? … Magna Mater! Magna Mater! … Atys … Dia ad aghaidh ’s ad aodaun … agus bas dunach ort! Dhonas ’s dholas ort, agus leat-sa! … Ungl … nngl … rrrlh … ckckck. …

Delapore’s language is imagined by Lovecraft as regressing through time, through Elizabethan and Old English to Latin and Gaelic, which is the last stop before asemic grunts. Gaelic is here seen as an earlier stage of civilisation – although it is a form of modern Gaelic that Lovecraft uses. Indeed, this Gaelic is lifted directly and without attribution from Fiona Macleod. The source is Macleod’s story The Sin-Eater, where it appears as a series of generic curses. However, as is usual with Macleod, the Gaelic is grammatically inaccurate and has no known native source.1 Lovecraft, seeking a representation of the ancient and unsophisticated, used instead a contemporary manufactured Gaelic from another author with weird ideas about the Celts. Lovecraft didn’t seem to mind such inaccuracies. When it was pointed out that Brittonic, from the other branch of the Celtic languages, would have been more appropriate to the story’s setting, he remarked “as with anthropology—details don't count. Nobody will ever stop to note the difference.”

Lovecraft’s ideas about Celts are, like Hugh MacDiarmid’s, a strange reflection of Macleod’s. On the one hand, stereotypical Celts – especially Irish Catholics – are staples of the savage cults in his stories, including major works like The Call of Cthulu and The Horror at Red Hook. These Celtic migrants are imagined, as in Sharp, as having some unique racial attunement to the mystical. On the other hand, Lovecraft imagines some racial advantage in having partial Celtic ancestry:

I think it is a great asset from the standpoint of fantastic literature to have so predominant a share of Celt [in one’s ancestry]. I have often thought, in surveying the trends of literature and socio-political organisation today, that the Celtic group is really the only young and unspoiled race left on the planet. All the rest of the white race has passed the naive and adventurous and life-loving stage of its evolution, and has reached that prosaic, urbanised, social-minded, unimaginative condition out of which vivid art finds hard work in growing. Only the Celt, I sometimes reflect, continued to think and feel spontaneously in poetic fashion – that is, in terms of symbolism, pageantry, dramatic contrast, and adventurous expectancy. In him we see the strongest remaining manifestation of the pure Aryan spirit – the spirit of the natural bard and fighter and dreamer as opposed to the merchant, the builder, the administrator, and the instinctive city-dweller

This is precisely the same image of the Celt as Macleod’s, with the key aspect that Celts are imagined as white, not as an other to whiteness, as may be seen in some texts, including contemporaries of Lovecraft. In Lovecraft’s settler-colonial context, Celts have become white, if of an inferior variety:

As for my attitude towards ancestral Celts — well, I fancy it’s still a bit ambiguous. I like ’em when they’re kings, yet after all mere Druid-hounds can’t compare in solidity & majesty with golden-bearded Vikings and conquerors. I’m for the Teuton in the last analysis — although of course a Celt or two on the loftier branches doesn’t poison a whole family tree!

As in Macleod, then, it is the destiny of Celts to be absorbed into the white supremacist project, offering a necessary mystical and adventurous gracenote. Too much Gaelic poisons the tree (and risks turning one into a deranged cultist of the elder gods), but a little strengthens the stock. Lovecraft couldn’t find a better hidden spirit for these ghastly ideas than Macleod.

A final curiosity worth mentioning is the source of the Latin that precedes the Gaelic. The Magna Mater refered to is Cybele, and Atys is her transfeminine consort. The house on the underground city is described earlier in the story as a temple to Cybele, which “thronged with worshippers who performed nameless ceremonies” and “orgies”. Of Atys, Delapole says she made him “shiver, for I had read Catullus and knew something of the hideous rites of the Eastern god”. In Catullus these are explicitly rites of castration and transfeminine becoming, and many other classical texts tell of Cybele’s transgender priesthood and their ceremonies of castration. Although Fiona Macleod seems never to have taken such a step herself, it is wonderfully appropriate that Lovecraft moves directly from Atys, notha mulier, to William Sharp’s transfeminine alter ego.

Fiona Macleod’s most famous ghost, beyond her name, is a book which has apparently nothing to do with her but its name. Carson McCullers’ 1940 novel The Heart is a Lonely Hunter takes its title from a typical Macleod poem, which I think is one of her finest, ‘The Lonely Hunter’:

Green branches, green branches, you sing of a sorrow olden,

But now it is midsummer weather, earth-young, sunripe, golden:

Here I stand and I wait, here in the rowan-tree hollow,

But never a green leaf whispers, “Follow, oh, Follow, Follow!”

O never a green leaf whispers, where the green-gold branches swing:

O never a song I hear now, where one was wont to sing

Here in the heart of Summer, sweet is life to me still,

But my heart is a lonely hunter that hunts on a lonely hill.

The novel features no green branches and no hunter, no dreaming fairies and lost Celtic nations, but it does feature an unending litany of unrequited desire, of characters, Black and disabled and tomboy, unable to find what they seek, or even name it. As Sarah Schulman has it,

[M]ost of her creations can be read as homosexual, repressed homosexual, future homosexual or dysfunctionally heterosexual. Albert Erskine (husband of Katherine Anne Porter, whom McCullers essentially stalked when the two women were at Yaddo together) reportedly finished reading The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter and declared, “That woman is a lesbian. I can tell from the author’s mind in that novel and by what she makes her characters do and say.” And yet there is not a single lesbian moment in the book[.]

In Schulman’s essay, this absence of consummated lesbianism somehow makes McCullers even more lesbian, as if gayness lies in longing itself. “In the absence of reciprocated lesbian love and the inability to consummate lesbian sex, McCullers still wore a lesbian persona in literature and in life. She clearly wrote against the grain of heterosexual convention, wore men’s clothes, was outrageously aggressive in her consistently failed search for sex and love with another woman, and formed primary friendships with other gay people.”

In this, McCullers has much in common with Fiona Macleod, another writer whose queer persona existed only as a pose, primarily in books and in letters to women. In both, there is a preoccupation with desire unfulfilled – indeed, unfulfillable. In Macleod, this finds a bizarre racial allegory in a fantasy of dwindling Celtic people, perpetually trapped in a heroic age and thus doomed to be absorbed by imperial drives; in McCullers, it is more commonly expressed through (rather more successful) portrayals of figures at the margins of America’s growing empire.

I’ve no idea if McCullers read Macleod carefully, or just came across a copy of From the Hills of Dream – still circulating in America as a popular text at the time – and took the line. She may have been led there by Helen Hopekirk, who set the poem to music with Macleod’s blessing, though the abbreviated text omits the line that became the title. Perhaps someone else read the poem to her and the line stuck in her brain, and any purported connection with Macleod – who, despite the longing, is as stylistically different from McCullers as it’s possible to be – is no more than a third-hand haunting.

One evening in 1970, Konrad Hopkins went to a seance. Just over a decade earlier, Hopkins had been the lover of the playwright Tennessee Williams (a great friend of Carson McCullers) for some four years, beginning when Williams invited Hopkins, then an Air Force sergeant, to his play. He became one of Williams’ regular “gentlemen callers”, though apparently an eager one. Hopkins claimed even to have come up with the title ‘Cat on a Hot Tin Roof’. Sadly, no trace of their correspondence remains in Williams’ published notebooks and letters.

Earlier still, when an undergraduate in the 1940s, Hopkins wrote an autobiographical novel whose hero was called Leonard Sharp. Midway through the novel Leonard becomes “his alter ego, his other, feminine self, whom he called ‘Leona’, a sort of feminisation of his own name”. As with Fiona Macleod, whom Hopkins had not yet read, Leona “gave free rein to [Leonard’s] imagination” and was “an independent life that had sprung full-grown from Leonard’s soul, an embodiment of the spirit of freedom and love”. The novel was never published.

In any case, twenty years later there was a seance, and the board spelled out a sequence of letters: F-I-O-N-A M-A-C-L-E-O-D. Hopkins now recognised the name, having come across Elizabeth Sharp’s biography and written a paper on Wilfion’s spiritual practises some months earlier. He began a conversation with that spirit, who was William Sharp, “and from that time to this, the conversation has not ceased”.

Thereafter, in the early months of 1970, Konrad’s mediumship progressed rapidly, in automatic writing, healing, clairvoyance, clairaudience, and psychometry, always under the loving guidance of William Sharp, who had been one of Konrad’s guides for many years, since before his Harvard days, and now became his ever-present friend and counsellor.

The quotations and biographical details here are from The Wilfion Scripts by “William Sharp / Fiona Macleod through the mediumship of Margo Williams”.2 Margo Williams, born in Kent in 1922 and living in the Isle of Wight, was another medium, who began communicating with William Sharp in 1976. William Sharp was only the second spirit to reach out to her, but in just four years there were “more than 360 Spirit communicators [who] have dictated to Margo over 4,000 scripts in prose and verse”. 92 of the new poems by Sharp are included in the Wilfion Scripts, which was published in 1980 after Konrad Hopkins saw mention of Williams’ mediumship (Margo, that is, not Tennessee) in My Weekly magazine. Hopkins had since settled in William Sharp’s home town, where he lectured in English at Paisley Technical College and founded a publisher named Wilfion Press. He couldn’t be more excited to publish Sharp’s new poems. As the book was being prepared, the spirit of the paleontologist Mary Anning (later played as a yearning lesbian by Kate Winslet) spoke to Margo Williams and said that William Sharp was delighted by the project, and that as a result “His Spirit is an etheric source of pink and silver”.

It has to be said that Sharp/Macleod’s poetic skills had somewhat declined in the afterlife:

Goblins bad,

Make me mad,

Pen-nibs crossed,

New ones lost.

My pencil’s broken,

Should not have spoken

Similarly, Sharp had gained a newfound sympathy for a form of Christian salvation and seemed to have abandoned his pagan ways. His habits of projecting his ideology onto racialised others and writing about pitiable figures of poverty, however, remained the same:

Children clutter

London’s gutter,

Covered in dirt,

Some slightly hurt.

Feet are bare,

None to care,

Little to eat,

Never have treat,

A reincarnation

Of souls in damnation

Margo Williams’ mediumship and ghost-hunting were covered regularly in the British press in the 1970s and 80s, though she faded from view in her later years. She died in 2009, and a book of her case files was published by her assistant in 2015. Konrad Hopkins passed over to join her and William Sharp less than a year later, after three decades as a prominent local figure at the heart of Paisley’s cultural scene. Whether William Sharp and Fiona Macleod have found anyone else to communicate with since I cannot say. Perhaps I should go to a seance and find out.

We die, and if we’re very lucky than our words live on for a few more years to be reinterpreted by others, in ways far beyond our control. Even when we dictate poems from beyond the grave, they emerge in forms unrecognisable to our living selves, offering ideologies we barely recognise. William Sharp summoned Fiona Macleod from his mind, or perhaps she summoned him into the world. Either way, once her spirit was loose she took on a life of her own. Now she is a parody Disney princess, a novel of lesbian longing, a proto-communist opera, a cannibal’s racist scream, a ghosthunter’s spirit guide, and the obsession of a Scottish transsexual trying to understand her own literary history. Wilfion could well be horrified by all of these interpretations. And yet, when in 1905 Helen Hopekirk wrote and asked for Wilfion’s permission to rearrange and abbreviate their poem for its musical setting, they wrote, “I do not think the needs or nuances of one art should ever be imposed upon the free movement of another in alliance.” They died two months later, leaving only such ghosts behind.

Notes

It was a squeeze to get this one out by my self-imposed deadline. Apologies if there are even more typos. As it seems I’m incapable of writing briefly here, I’m considering switching to a monthly rather than a fortnightly schedule. My hope is that this will enable me to continue to write well-researched pieces here, rather than rush out rambles, and also that I will be more able to finish my next book. I have one more piece on Sharp and Macleod, an epilogue which I’ll write for May 1st, and then move to the new mode.

On 27th April I’ll be at Lyra Bristol Poetry Festival, in person and online.

I’ve helped to launch The Quine Report, a data-led analysis of sexism in Scottish literature. Please follow its author, Dr Christina Neuwirth, here on Substack for the full report in installments.

This insight and the analysis that follows is drawn from Duncan Sneddon’s excellent paper, ‘The Celt’s far vision of weird and hidden things’? H. P. Lovecraft, William Sharp and the Celts

Endless thanks to Caoimhe McMillan for finding The Wilfion Scripts.